“Rarely, if ever, are any of us healed in isolation.

Healing is an act of communion.”

Bell Hooks, All About Love

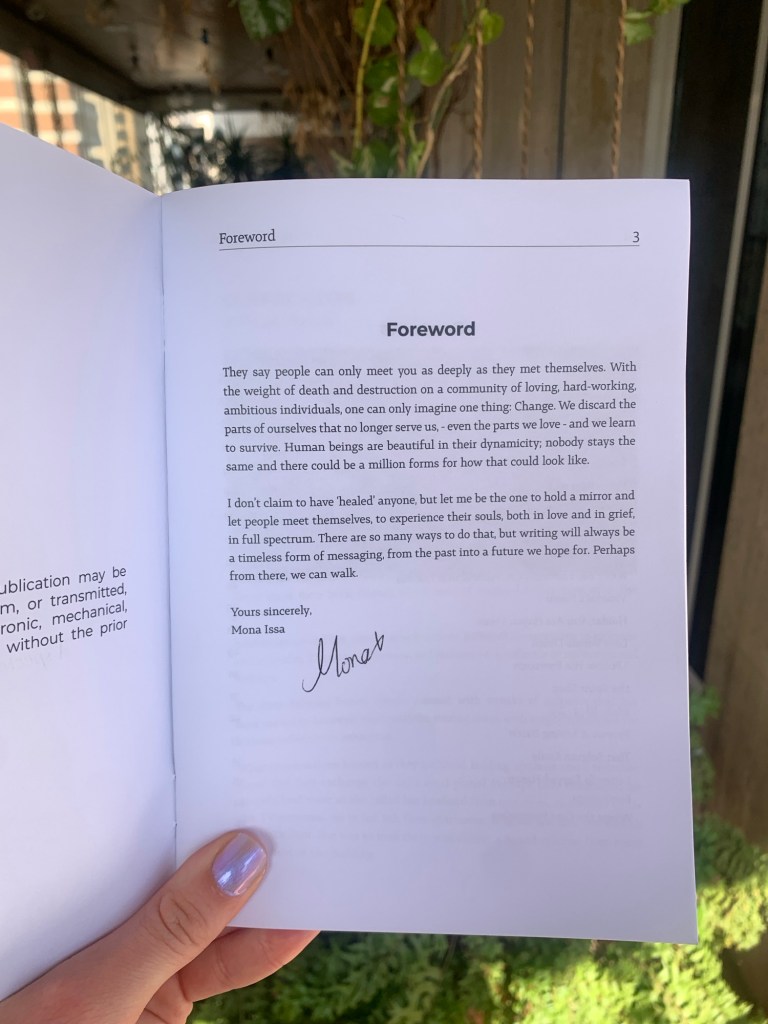

In January, with relative calm returning to Beirut following the ceasefire announced on November 26, 2024, I attended a three-day writing workshop. The event was titled “Unfinished Battles: Post-War Writing Workshop,” and its flyer invited participants to “Join a fearless space and transform your pain into powerful art.” It was run by Mona Issa, a psychology graduate turned writing coach, passionate about literature, healing through storytelling, and building bold, creative communities.

Attending the workshop was an opportunity to connect with others, from different walks of life, who had lived through the war. I learnt alot. Everyone brought their own unique and layered experience. While we all shared a sense of injustice, and a loss of security and control, the impact was uneven. Some neighborhoods were heavily bombed; others, like mine, remained relatively intact. Those with the means questioned whether to leave or stay —a decision that for many carried complicated consequences for families, communities, and people’s sense of identity. Some people lost their homes; some people lost loved ones. All of us were changed by the war, though we’re still working out exactly how.

What Mona did with this workshop was to create a space to reflect, both personally and collectively. With her guidance, and through the targeted exercises, we began to confront what we had lived through, and to make sense—if only in fragments—of the chaos and grief that surrounded us. After the workshop, I asked Mona if I could interview her for my blog.

It’s worth noting that since the ceasefire announcement, according to UNIFIL data there have been over 2600 air violations by Israel and more than 60 airstrikes (all by Israel into Lebanon). Israel has killed more than 71 civilians in Lebanon since the ceasefire. There have been no reported casualities on the Israeli side. This is why when I talk about ‘post’ war I am using inverted commas; because, as somebody raised at the workshop, in some neighbourhoods, the war doesn’t feel over; it feels very much ongoing. Resources like this public database from the Center for Information Resilience and these datasets and analyses from Armed Conflict Location & Event Data (ACLED) help to document these ongoing patterns of violence and make verified data more accessible to the public.

Many faces

“A person is a fluid process, not a fixed and static entity; a flowing river of change…..a continually changing constellation of potentialities…..”

Carl Rogers, On becoming a person

My first question to Mona was what inspired her to create the post-war writing workshop. “I, myself was coming out of a very difficult experience during the war” Mona told me, “and I was also navigating through my life, through my emotions, through the weathers. There are many different faces of post-traumatic stress that your body and your mind experience after going through something difficult. I am someone that believes that my experience is unique and nobody can have what I have. Nobody can experience what I have experienced”.

Mona went on, “and I wasn’t just navigating the event itself, but also learning about me as a person. And that has also driven me to pursue things that I’ve been wanting to pursue for such a long time, but for different reasons and different motivations, in different contexts. And you know, something Chrissie, we heal in so many different ways as we move forward in life“.

“I felt (not consciously though), but I felt that one of the ways where I can heal is through fulfilling at least parts of my goals, parts of my dreams. And that also includes helping and networking with people – with not necessarily like-minded people, but people that have also experienced this event with me”.

Channeling, Creating

“The past doesn’t disappear.

The past needs to be digested.”

Thomas Hübl, Healing Collective Trauma

Mona continued, “We might not have been crying together… and we haven’t necessarily been grieving together. But the fact that you walked into that classroom with a certain mindset—ready to channel your feelings and your experience into something creative, into art—that means the world to me. It fulfills me, not just as Mona who carries trauma, but as Mona the person. Even the child in me felt a kind of joy—she was jumpy and happy. It was, truly, an Ikigai moment.” Mona laughed.

I love how Mona so openly acknowledges the many parts of herself. I feel her actively resisting any attempt to reduce her life to a single story. She claims her complexity, unapologetically—and invites the rest of us to do the same.

“I’ve always been a writer” Mona told me. “I’ve always been a people person. I mean, I can be a social grouch, sometimes” she laughed. “But I do love human beings. I think that was my main driving purpose”.

Space

“There is no greater agony

than bearing an untold story inside of you”

Maya Angelou, I know why the caged bird sings

Mona’s workshop made me reflect on how profoundly place shapes our inner lives—not just our movements, but our ability to feel, reflect, and exist with a sense of self. For many, the war was experienced in overcrowded homes, surrounded by extended family, sounds of airstrikes, and collective anxiety. In those conditions, there was little space—physically or emotionally—to process what was happening. Simply stepping into a different environment, like the workshop, offered a rare sense of privacy and calm. That shift alone created room for people to breathe, to think, and to reconnect with themselves. Mona told me “I think that we sort of take for granted how much places and our surrounding have an effect on us. Some places can create trauma for you, some places can make you feel safe and loved and welcomed. Whenever I’m feeling a particular way, I think about the place that I’m in. Do I need to change the place so that I can change something within myself? And in many cases, yes, it does have an impact”.

“Creating that space in the workshop was so important,” Mona told me. “Even though it was underground, in a café… it didn’t matter. As soon as we closed the door, we shut the entire world out. Inside, you were no longer in a place where you needed to wear a mask. That’s something I kept repeating to my students: ‘Your mask won’t serve you here. You are safe. You are free to express yourself.’“

“And I saw it—people who don’t usually cry, suddenly crying. People really beginning to connect with who they are. They were finally sitting with their emotions. And you don’t have to bring it all out in the workshop—that’s a hard thing to do, and I don’t encourage it if you’re not ready. But just sitting with your feelings, even for a moment—that alone means something. That alone is enough.”

I was struck by how intentionally Mona created not just a physical space, but an emotional one—an atmosphere that gently invited people to loosen their grip on survival, and simply feel.

“And just to add to that point about the importance of space,” Mona said, “I’ve been in Lebanon for a while now, and it’s not about escaping reality—but part of my healing is being able to shift focus to other parts of my life. I spent some time in Rome, then in Sydney, and those places helped nourish me. They gave me the strength to feel, to process, and eventually return home more ready to face the harder realities of everyday life.”

Flow

“The medicine is already within the pain and suffering. You just have to look deeply and quietly. Then you realize it has been there the whole time”

Saying from the Native American oral tradition

I asked Mona how the workshop came together and what the process was like for her personally. “It was a blend of things, but the structure of the workshop came together naturally,” Mona explained. “I’m not drawn to things that feel like a constant struggle—if something drains you, maybe it’s not meant for you, at least not at that time. This workshop didn’t take energy from me—it gave me energy. I was excited to be there. I didn’t feel nervous or unprepared like I usually might. It just flowed. Of course, I used strategies and thought about why I used them, but they were subtle, almost intuitive.”

Many elements of Mona’s workshop could be seen as what psychologists call “therapeutic agents”—the ingredients that support trauma integration. There is some research for example that suggests that writing authentically and expressively, in a way that links feelings to events can help integrate our physiological and emotional responses with the broader context of time, place, and meaning. It allows us to process trauma not just cognitively, but somatically; and in turn this can also lower our blood pressure, improve our sleep, and help to ‘free up’ cognitive resources.

In many ways, this empirical research is only affirming much of what communities have long known: that healing is already embedded in the practices, traditions, and instincts people turn to in times of pain. What made Mona’s workshop powerful wasn’t just the techniques, but the way they emerged with ease, rooted in cultural rhythm and meaning. For healing to work, it has to flow—not just from the facilitator, but from the people and places it’s meant to serve.

Compassion as resistance

It struck me that an important aspect of Mona’s initiative comes back to identity—how essential it is to hold onto a sense of self after trauma. Grounded in an anti-colonial framework, Mona framed the workshop not as a space for victims, but as a space for people actively resisting, processing, and creating. It offered a way to reclaim dignity through expression, and to do so collectively. We also listened to each other. When I think about it, the workshop did a lot more than it appeared to on the surface.

Mona said “Something I always say is that hope is an act of resistance—especially in the face of oppression. Any oppressor, anywhere in the world, is trying to take something from you. And it’s not just land or resources. They try to take your hope—your belief that you are worthy of dignity and respect”.

“Once that hope is gone, everything else begins to fall away. You lose the will to struggle, the energy to fight. Losing hope is, in many ways, surrendering completely. That’s why holding onto a positive self-image—acknowledging what you’ve been through and still choosing to care for yourself—is also a radical act. It’s a form of self-preservation the oppressor hopes to break”.

“Compassion—for yourself and for your people—is a form of resistance too. It’s empathy, it’s humanity. It’s the refusal to judge each other while recognizing the deep, layered trauma we carry as individuals and communities. And it’s the understanding that healing is not separate from liberation—it’s part of it….Because liberation isn’t just about reclaiming land, though that’s essential. It’s also about reclaiming the self—the heart, the spirit, everything that’s been suppressed or broken. And as long as we hold on to that hope with everything we have, we still have the will to fight—and, insha’Allah, to succeed.”

“We believe in that. It’s not just a hopeful idea; it’s rooted in faith, in culture, in history. And I hope we can always return to that truth when we’re faced with the cruelty and injustice in this world”.

Humanity

Mona’s words resonated. They led me to reflect more deeply on how the trauma we carry is not a mark of failure or defect. It is, in fact, a testament to our humanity—our capacity to feel deeply, to endure, to resist, and to remake meaning in the aftermath of harm. It speaks to our strength, our complexity, and our right to be shaped by our experiences without being defined by them.

In a region where trauma is not something left behind, but something actively inflicted—where people continue to be bombed, dispossessed, and dehumanized—this truth demands recognition. Healing here isn’t a tidy aftermath; it’s a form of resistance in the midst of ongoing violence that Western frameworks often fail to grasp. It’s less about ‘getting better’ and more about insisting on your full humanity, even when the world tries to deny it.

Thank you, Mona, for the generosity of your words, and for reminding us that healing is not simply a psychological process, but a social, political, and ethical one—one that demands context, care, and and a commitment to dignity.

Our writing

Mona has nurtured our writing with patience and insight, and has now brought it all to life in this beautiful book! It’s available at the Beirut Arab Book Fair until the 25 May, in Seaside Arena – AKA BIEL. The fair is open daily from 10.00am – 9.00 pm and you can find the stall in A10.