I’m spending May/June in beautiful Izmir, Turkey with Imece Initiative, an NGO which helps displaced people and refugees in Turkey by implementing education and empowerment programs to create sustainable and fair change.

Over the last 4 weeks I’ve gotten to know some women facing incredibly harrowing situations. I’ve learnt more about what it really means to have no safe choices. Women who have had their families torn apart, have lost children, face violence, have nowhere to go.

Nadire Abla

I’ve also gotten to know Nadire Abla, who works here at Imece and spends each day creating a safe space for these women and their children to come together, learn and heal. She feeds and cares for the children, fights fiercely for women to navigate the Turkish system, and supports families to get legal and medical assistance, and be able to rebuild their lives.

Abla reminds us all to lean on each other… and to laugh together! When things feel too overwhelming, I’ve seen Abla with tears in her eyes but still being cheeky and full of life. We barely speak a word of each others languages but that doesn’t matter. From the moment I met Abla she was so welcoming and caring.

“Galloping from farthest Asia

and jutting out into the Mediterranean

like a mare’s head—

this country is ours.

Wrists in blood, teeth clenched, feet bare

on this soil that’s like a silk carpet—

this hell, this paradise is ours.

Shut the gates of servitude, keep them shut,

stop man worship another man—

this invitation is ours.

To live, free and single like a tree

but in brotherhood like a forest—

this longing is ours.”

Invitation, a poem by Nazim Hikmet and translated by Taner Baybars. Chosen by Nadire Abla.

I asked Abla 3 questions using google translate. Abla wrote me beautiful answers in Turkish. A mutual friend, Rojda Pekyen kindly helped to translate Abla’s answers into English, which you can read below. This blog post cannot not fully do justice to the deep meaning from Abla’s original words written in Turkish. I have also included the original answers in Turkish on the link on the button below, if interested.

A little Kurdish village

“I was born in a small village in the east of Turkey, where the population does not change much, and has only been decreasing over the years”, she told me.

“There were intense political tensions in the region I am from, as well as inadequate educational and economic opportunities. So my family migrated to Izmir, the westernmost city of the country. So when you look at it, I am also an immigrant, of Kurdish origin”.

I asked Nadire Abla what the name of her village is. She told me it’s name was stolen. The locals have always called it Margik. But the Turkish state changed the name to Günboğazı as part of a policy of ‘turkification’. I did some of my own research and found that Margik is in a province that is now officially called Tunceli, but that used to be called Dersim. Until the 19th century, when the Ottoman Empire began transitioning into a modern centralized state, it was relatively independent, as was most of the Kurdistan region.

Dersim was a symbol of uprising and resistance against the assimilation policies of the young Turkish republic. In 1937-38 an estimated 40.000 people were massacred when the Turkish army cracked down on insurgents.

“Perhaps this is what enabled me to establish deep bonds with these people who came to Anatolia as guests. I always feel like an immigrant in my own country” Nadire told me. Nadire has been working with displaced people and refugees for 10 years now, from the mid-2010s. In Imece she is mainly working with refugees from African countries. At the moment it is mostly Congolese and Angolan refugees.

“In some sense we are all immigrants at some point in our family history. We all follow in the footsteps of the first human to walk upright. We can be considered as passengers on the journey of life.” She added “- in some sense we are all immigrants from the African cradle”.

At the Same Table

I asked Abla what the best part about her job is. “I’ve never been outside of Turkey. I’ve not had much opportunity to travel except for the migration from the village where I was born to the West of the country. But through this work with refugees I have had the opportunity to learn the traditions and customs of people from many different countries. We all have so much in common….

When we sit at the same table and eat and drink together we all share a common understanding and feelings of humanity. Even if we don’t actually speak each others languages we can all understand when we see a sincere look, a smile. At the table, no one’s race, religion, or politics is visible. As you see, whether we are Kurdish, Turkish, Arab, Italian, Taiwanese, French, Scottish, – we are all humans, people of the world. The most important common denominator of all of us who share the same laughter from our places is that we are an ‘aware person’.”

“The famous Turkish poet Nazım Hikmet told us this in the lines of one of his poems”:

“Brothers and sisters,

never mind my blond hair,

I am an Asian;

never mind my blue eyes,

I am an African….”

-Nazam Hikmet, from poem ‘To the Writers of Asia and Africa’, 22 Ocak 1962.

“This is the most amazing thing for me about this work and effort. I have collected friends from many parts of the world….I may not appear rich in money, but I am so rich. The refugees as well as me, we are rich in humanity. I feel I am so human”.

Bleeding Wounds

I asked Nadire Abla what the hardest thing is about her job. “Every day, finding ourselves in the middle of problems creates moments of overwhelming despair. Sometimes you cannot feel fully present at home with your family. While feeding your child at home, you want to laugh, but you cannot laugh or be happy about something good, because there is always something “missing, broken, sad” inside of you. It impacts on your life – the time you spend with your friends and relatives… Always in the back of your mind you’re feeling you are missing something. You are not complete. A little piece of you is feeling the desperate suffering of the people, and especially children, finding themselves facing insurmountable challenges at such an early age.

You are often trying to think of solutions to the arbitrary attitudes of law enforcement and other local bureaucracy forces. We have a folk saying: “The eye sees, but the arm is short.” We see so much but we have limited resources to solve these problems”.

“People have wounds that cannot be healed and are constantly bleeding. We have limited resources to help them.

We are witnessing this every day, – not from the outside, but by being in the middle of it.

And the pain you witness doesn’t leave you”

Nadire Abla

“It’s like we are holding the end of a thread from the ball of problems, but the ball keeps rolling. The problems continue to get heavier and accumulate; we follow those problems by the end of the rope we hold on to.”

Drifting

“We often feel like we are drifting. It can feel like you no longer have a homeland. Suddenly you don’t have the capacity to fall in love or connect with your emotional memories. The streets you know, your friends, the people you see each day greet each other like always, but you are just focussed on the latest problem or situation. You are no longer carefree. You no longer stop to idly pet a dog that is wagging it’s tail; your childhood sweethearts don’t exist in your memory in the same way anymore… Your don’t have the same innocent joy. It’s not the same”.

Stateless

“When you are stateless, you are ‘placeless’, ‘homeless’. You look like a human, but the local people don’t see you as a human being. If you don’t have an ID or a passport, you are seen as a “burden” that needs to be expelled from the country. You are targeted as an object of hate by racists….so much so that sometimes central governments or local politicians make targeting stateless people their primary issue, as opposed to solving the poverty of their own people. When you are stateless, the government can use you as a target, as a scapegoat for everything they are not doing.

We all have labels imposed on us: refugee, asylum seeker, immigrant or local. But these bureacratic labels reduce our own humanity too. You are someone, a whole person with a complex and rich lived experience with memories and loves. These labels reduce us, to a name, a passport or ID number.

We are striving to treat the wounds of people who are hurting and struggling. But we can’t cure the problem unless we also struggle against these reductive attitudes. The attitude of only seeing a persons colour for example. We need to move past seeing ‘colours’ and see whole humans.

Does this struggle seem so hard? Yes, it is hard. But it is also something that makes me so proud”.

Abraham and Nimrod

“It is a famous story. The story of Abraham and the cruel king Nimrod.

When Prophet Abraham was cast into a fire by the tyrant king Nimrod, the spectacle was met with horror by a small ant. It ran as quickly as it could to a nearby river, where it picked up a leaf and filled it with water. The ant carried these meagre drops to where the fire was lit before going back for more. The water it fetched was of course, not enough to quell the raging flames. An arrogant crow mocked the ant’s scurrying efforts and haughtily told him: ‘Hahaha, you fool. How can you hope to douse the fire with such little water. Surely you realise that there is nothing you can do?’ “Okay” said the ant, whose beard turned red with the flames of the fire. Calmly and unperturbed he replied: ‘When I meet with God, He will not ask me whether I was able to put out the fire, He will only inquire whether I did my part to see that it was extinguished.’

This is the ancient question: Whose side do you want to take? Will you try to do your bit for Abraham (they also call him “father of the peoples” in his own language) or will you take the side of Nimrod, who threw Abraham into the fire? In a way, we are also like this ant. We know we won’t fix all the problems but at least we are doing something. In this way, we are showing are solidarity”.

An African Proverb

I asked Nadire Abla what her message to the world would be. “They once asked an ancient philosopher who lived in Anatolia before Christ “What is the World?”

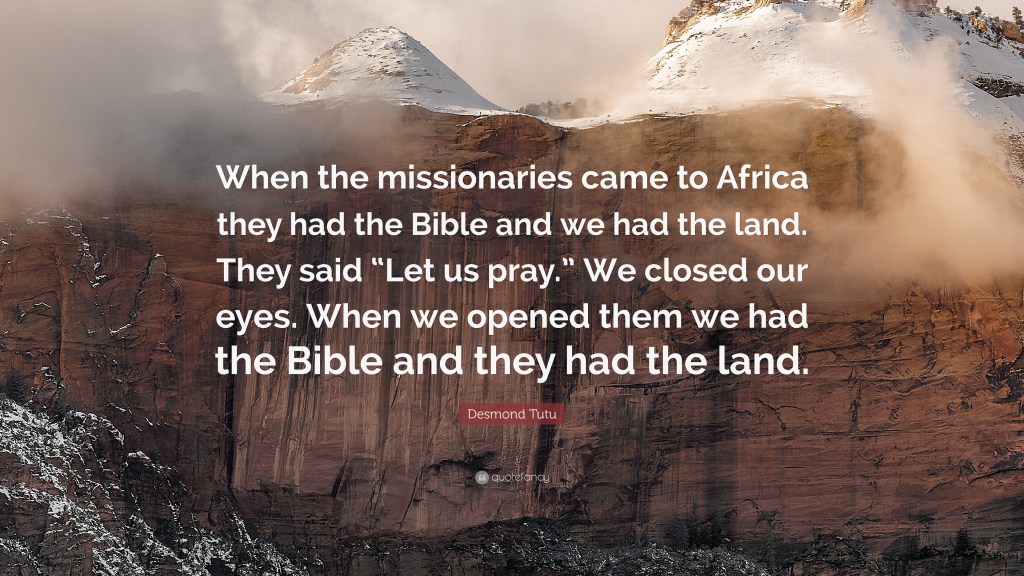

“It is our common home,” he replied. But it didn’t happen that way. After God created the world, humans began to think that their gods were greater than other peoples gods. People started to use religion to justify the degradation of others, to justify wars. A blind mentality dominated, people were enslaved to those who claimed to be God and his representatives on Earth. They built temples… During the long middle ages, women healers were burned at the stake. ‘Explorers’ crossed the ocean and saw people who had been living freely on their own land for hundreds of years. However, if those ‘natives’ who had been ‘discovered’ had been asked, the explorers would not have been called explorers at all, but would have gone down in history as ‘murderers’. Christopher Columbus saw these people had nothing in their hands other than the small spears they used to hunt to get enough food. When he saw this, he wrote in his letter to the queen, “We will destroy the whole continent with fifty armed men.” In this story too, there was a priest with a Bible next to Christopher Columbus.

Africans have a proverb: “They came. They had the Bible in their hands. We lived and lived in this vast land, even though we sometimes fought. Then we closed our eyes and prayed with beautiful, sweet words. We had the Bible now, but it was vast. The lands became theirs and we became slaves in our own lands.””

Abla is saying this is a context where Erdoğan, who has been Turkey’s leader since 2003, is seen by some as increasingly exploiting religion as a tool for political gain and control.

From Slums to Palaces

“The owners of the Empires Where the Sun Never Sets brought all the wealth to their own countries. All the riches of Asia, Africa and Latin America have been used for centuries by today’s ‘civilised first world countries’. What is happening all over the world right now; the rise in migration, the rise in racism, fear, and hostility is a never-ending cycle. History is repeating itself. We need to remember our history with a critical eye. We must acknowledge the bad parts of our histories.

Just as the proud victors in the First and Second World Wars also convicted the losers to indemnity (Germany only finished paying back it’s dues in 2010). We must also require yesterday’s colonizers to compensate for the damage they have done to the world order. If we (the colonisers) don’t acknowledge our troubled past and histories and compensate those who we subjugated and colonised, then we are condemning the worlds poor to pay compensation for our own mistakes. We cannot keep running away from the the problems we created, we will have to pay the compensation in some way or other whether we like it or not.

At the moment, the Western governments want to make Anatolia a warehouse to keep refugees there. However, this can’t work for long. Bribery, charity or other measures given by unions such as the UN and the EU are only putting a plaster on the wound, but they are not healing the injuries. If we don’t start to address the root problems and allow people to claim for historic damages, sooner or later the lights of the palaces go out. If you look at the inequality in the world, what I say will make sense. If there is no justice for the slums of the world, the palaces will be doomed to burn”.

Hope

Imece’s motto is ‘Empathy makes us human’.

At times like these, it is easy to look at all the suffering and feel deeply hopeless.

Abla, gives me hope. She reminds me that true strength in the face of suffering and injustice is to stay fiercely compassionate, hold on to your brightness, and stay human.

Nadire Abla, thank you so much for sharing your story and your beautiful words.